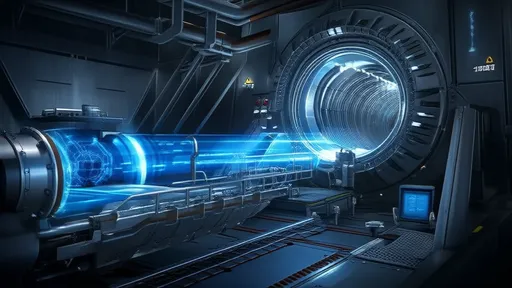

The concept of transmuting nuclear waste using accelerator-driven systems (ADS) has long been a topic of both fascination and controversy in the realm of nuclear science. Unlike conventional reactors, which primarily generate energy through fission chain reactions, ADS employs a particle accelerator to produce high-energy protons that, in turn, trigger spallation reactions in a heavy metal target. The resulting neutrons are then harnessed to transmute long-lived radioactive isotopes into shorter-lived or even stable elements. This approach offers a tantalizing solution to one of nuclear energy's most persistent challenges: the disposal of high-level radioactive waste.

The science behind ADS is as complex as it is promising. At its core, the system relies on a high-power proton beam—typically in the range of hundreds of MeV to a few GeV—striking a dense target material like lead or tungsten. The impact generates a cascade of neutrons, far more abundant than those produced in traditional fission reactions. These neutrons are then directed into a subcritical reactor core loaded with nuclear waste, where they induce fission or capture reactions that alter the isotopic composition of the waste. The result is a reduction in both the radiotoxicity and the half-life of the remaining material, potentially transforming what was once a millennial-scale hazard into a more manageable byproduct.

What sets ADS apart from conventional reactors is its inherent safety profile. Because the system operates in a subcritical state, it cannot sustain a chain reaction without the continuous input of neutrons from the accelerator. This eliminates the risk of runaway reactions or meltdowns, a concern that has haunted traditional nuclear power since its inception. Moreover, the ability to "turn off" the reaction simply by stopping the proton beam provides an additional layer of control that is absent in critical reactors. For many proponents, this makes ADS not just a tool for waste management but a potential cornerstone of next-generation nuclear energy systems.

Yet for all its theoretical advantages, ADS faces significant technical and economic hurdles. The accelerators required for such systems are extraordinarily demanding, needing to deliver proton beams with unprecedented reliability and power. Current technology struggles to meet these requirements without frequent maintenance or downtime, which could undermine the economic viability of large-scale deployment. Additionally, the materials used in the target and surrounding structures must withstand extreme conditions—intense radiation, thermal stress, and corrosive environments—over extended periods. Finding or developing materials that can endure such punishment remains an active area of research.

The financial and political dimensions of ADS are no less daunting. Building and operating an ADS facility would require substantial investment, likely running into billions of dollars. Given that nuclear waste management has historically been a low priority for many governments, securing funding for such projects is far from guaranteed. Skeptics also question whether the benefits of transmutation justify the costs, particularly when alternative waste disposal methods, like deep geological repositories, are already being implemented in some countries. The debate often hinges on long-term risk assessment—weighing the uncertainties of untested technology against the known challenges of existing solutions.

Despite these challenges, research into ADS continues to advance, driven by both national and international collaborations. Countries like Japan, China, and several within the European Union have invested in experimental programs aimed at demonstrating the feasibility of various ADS components. The MYRRHA project in Belgium, for instance, represents one of the most ambitious efforts to date, aiming to construct a functional ADS prototype by the 2030s. Such initiatives are not just about waste transmutation; they also explore the potential of ADS for producing medical isotopes or even serving as a versatile neutron source for scientific research.

The ethical implications of nuclear waste transmutation cannot be overlooked. On one hand, ADS offers a way to mitigate the intergenerational burden of radioactive waste, effectively addressing the moral dilemma of leaving hazardous materials for future societies to manage. On the other hand, some argue that focusing on technological fixes like transmutation may divert attention and resources from more immediate solutions, such as reducing nuclear waste production through improved reactor designs or renewable energy alternatives. The tension between innovation and pragmatism is a recurring theme in discussions about ADS and its role in the broader energy landscape.

Looking ahead, the future of accelerator-driven transmutation remains uncertain but undeniably intriguing. Should the technical obstacles be overcome, ADS could revolutionize how humanity deals with nuclear waste, turning a liability into an opportunity for cleaner energy production. Even if the technology never achieves widespread adoption, the research it inspires may yield spin-off benefits for other fields, from accelerator physics to materials science. For now, the pursuit of ADS stands as a testament to human ingenuity—an attempt to solve one of the most stubborn problems posed by the atomic age.

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025

By /Jul 18, 2025